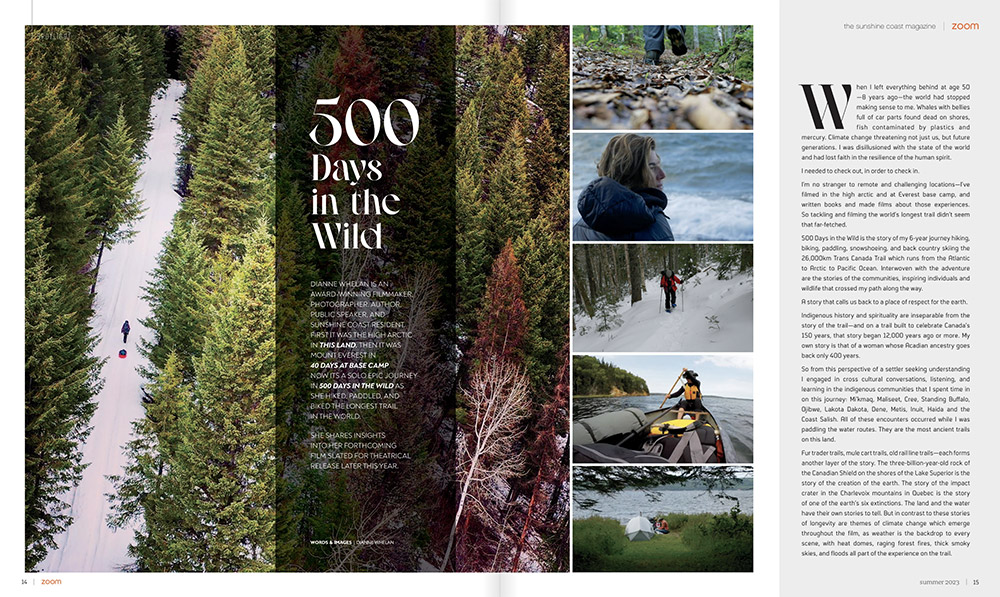

Dianne whelan is an award-winning filmmaker, photographer, author, public speaker, and sunshine coast resident. First it was the high arctic in this land. Then it was mount everest in 40 days at base camp. Now it’s a solo epic journey in 500 days in the wild as she hiked, paddled, and biked the longest trail

in the world. She shares insights into her forthcoming film slated for theatrical release later this year.

When I left everything behind at age 50—8 years ago—the world had stopped making sense to me. Whales with bellies full of car parts found dead on shores, fish contaminated by plastics and mercury. Climate change threatening not just us, but future generations. I was disillusioned with the state of the world and had lost faith in the resilience of the human spirit.

I needed to check out, in order to check in.

I’m no stranger to remote and challenging locations—I’ve filmed in the high arctic and at Everest base camp, and written books and made films about those experiences.So tackling and filming the world’s longest trail didn’t seem that far-fetched.

500 Days in the Wild is the story of my 6-year journey hiking, biking, paddling, snowshoeing, and back country skiing the 26,000km Trans Canada Trail which runs from the Atlantic to Arctic to Pacific Ocean. Interwoven with the adventure are the stories of the communities, inspiring individuals and wildlife that crossed my path along the way.

A story that calls us back to a place of respect for the earth.

Indigenous history and spirituality are inseparable from the story of the trail—and on a trail built to celebrate Canada’s 150 years, that story began 12,000 years ago or more. My own story is that of a woman whose Acadian ancestry goes back only 400 years.

So from this perspective of a settler seeking understanding I engaged in cross cultural conversations, listening, and learning in the indigenous communities that I spent time in on this journey: Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Cree, Standing Buffalo, Ojibwe, Lakota Dakota, Dene, Metis, Inuit, Haida and the Coast Salish. All of these encounters occurred while I was paddling the water routes. They are the most ancient trails on this land.

Fur trader trails, mule cart trails, old rail line trails—each forms another layer of the story. The three-billion-year-old rock of the Canadian Shield on the shores of the Lake Superior is the story of the creation of the earth. The story of the impact crater in the Charlevoix mountains in Quebec is the story of one of the earth’s six extinctions. The land and the water have their own stories to tell. But in contrast to these stories of longevity are themes of climate change which emerge throughout the film, as weather is the backdrop to every scene, with heat domes, raging forest fires, thick smoky skies, and floods all part of the experience on the trail.

Solitude reveals what a mirror cannot. It is a very grounding experience to be in nature alone for weeks at a time. Also, in accepting that no one will rescue you if things go sideways, you have to accept the responsibility to save yourself if something goes wrong. It is a very humbling experience to be a fragile being alone on the vast waters of Lake Superior or deep in the woods on an old fur trader trail in Quebec. But then something ancient wakes up in your DNA, and you feel more connected to life than you ever have.

My solitude was occasionally relieved by sharing parts of the trail with fifteen women. Five are indigenous women, five are queer women. Four of the women joined me at least twice on the journey and stayed for at least two weeks. All four are close friends and all between 40 and 60 years old.

These women experienced some extreme challenges with me. Jenica and I were stranded in the middle of a 1200km wilderness paddle after a massive snowstorm and unseasonal cold temperatures froze the water of the lake we were paddling. Snowshoeing the Voyageur trail in the woods above Huron Lake in winter we also ran out of food because the unexpected difficulty of the trail added days to the journey. In 2019 Louisa and I paddled the 4000km to Tuktoyaktuk, encountering wildfires and aggressive wildlife, while also dealing emotionally with the deaths of two people also on the same trail. One drowned, the other was killed by a grizzly bear, and this had a profound effect on us.

And then there all the many different times when I was helped by strangers. As an example, I got lost at night in a bad storm in Nova Scotia. I was terrified. Never a good feeling lost alone in the woods. I was pushing my heavily packed mountain bike up what was a dirt hill but now a streaming brown river. Then I saw distant lights coming towards me, and in my fearful state, instead of seeing help, I saw only my vulnerability as a woman alone in the middle of nowhere. I saw two men in camouflage, with hunting guns, drinking rum. I didn’t want to trust them, but my fears were quickly dispelled by these two very kind people who brought me to shelter and warmth, fed me a meal of deer meat, and smoked a cigar with me. They showed me on maps where I was, where I made a wrong turn and the next morning brought me back to reconnect to the trail.

On the very last paddle of the trail, I battled huge swells on the Salish Sea before arriving on a beach in Victoria, a short walk from the mile zero marker. The daughter of the late Chief of the Songhee people, Cecelia Dick, was on the shore awaiting my arrival and welcomed me to shore, while tears ran down my face as I recognized that the physical journey was done.

And now I have been working with a team of producers, editors, graphics and animation people, a composer, and a sound designer, all dedicating their time and experience to help me create a great feature film out of 800 hours of footage and thousands of stills. Support has come from a long list of individuals, government agencies, foundations, our distributor Elevation Pictures and our broadcast partner Paramount+.

I was profoundly changed by this experience:

When I left, my spirit had been broken, I wanted to be alone and I pushed love away. But in the fourth year of the journey I began a relationship with a woman who has been my friend for a decade. By the end of this extraordinary journey I have found love, hope and a passion to share a story that connects us all to each other and to the past and the future.